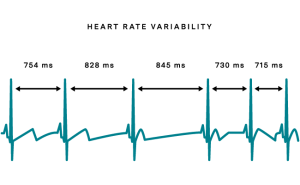

HRV is the root mean square of the difference between heart beats

Editor’s Note: As new devices like heart monitors become available for horse owners and riders, we think it’s important to understand their potentials and limitations. Technology often outpaces our knowledge base, making the setting ripe for misinterpretation and misinformation. Take a moment to educate yourself and have fun in the process. Connecting with horses may be facilitated by a device, but it’s always about taking time and being present.

In Part I of this examination of heart rate variability [HRV] monitoring, we discussed how HRV allows us to monitor the activity of the autonomic nervous system. We continue here with a look at its potential with horses and the horse-human connection.

Translating HRV data from animals is fraught with challenges. For starters, the waveform of electrocardiograms of hoofed mammals is not the same as ECGs of humans. Plus, most animals don’t make good clinic patients. Just the simple act of moving requires scientists to devise a method for adjusting HRV readings to something meaningful and relevant while subjects are active.

In this study with sheep and cattle , researchers accounted for movement as “dynamic body acceleration” [DBA]. They attached accelerometers (to account for changes in DBA) and HRV monitors to their subjects. They discovered through calculated review that animals grazing on pasture were less stressed than those in confinements. They write: “We quantitatively and continuously confirmed that the stress levels of the free-moving animals within the grazing system were less than those in animals within the housing system, based on the results of the HRV analyses.”

, researchers accounted for movement as “dynamic body acceleration” [DBA]. They attached accelerometers (to account for changes in DBA) and HRV monitors to their subjects. They discovered through calculated review that animals grazing on pasture were less stressed than those in confinements. They write: “We quantitatively and continuously confirmed that the stress levels of the free-moving animals within the grazing system were less than those in animals within the housing system, based on the results of the HRV analyses.”

Those findings notwithstanding, slapping an HRV monitor on a horse and drawing immediate conclusions (“he’s relaxed” or “she’s anxious”) is ill-advised. Consider, too, that when you are monitoring a device, you’re necessarily taking yourself from full focus of the horse itself and the tiny changes in behavior (a weight shift, an eye blink, a breathe out) that might help you assess its well-being.

West Taylor at BHPS

West Taylor, who runs science-based seminars, has presented at the Best Horse Practices Summit, and has an excellent understanding of how science can be applied to horse training, started using an HR and HRV monitor this year. While he’s making observations and taking lots of notes, he’s humble about his deductions and has visited many times with Dr. Virgil DiBiase, a neurologist with a strong familiarity with HRV and the ANS.

Writes West:

The biggest value I’ve found in monitoring HR and HRV is in waiting longer for the horse to fully mentally recover from whatever the stimulus was. I’ve felt like I waited a decent time, then I’d look at the HRV and see that the horse was still scoring in the sympathetic range (low HRV).

Longer wait times result in deeper learning and calmness. My biggest take-away by far from using science-based horsemanship is: If we slow down faster, we get done sooner.

Barry tries on an HRV monitor while we view metrics on phone

Watch his Best Horse Practices Summit presentations here and here.

During a recent visit with Taylor, we placed HRV monitors on two of my horses. As supported by research, we found that higher HR correlated with lower HRV. More movement also meant higher HR and lower HRV readings, generally speaking.

HRV measurements are most valuable when the animal is resting and not valuable at all when the HR is over 120, said DiBiase. We worked accordingly: horses were standing or walking and their heart rates were not elevated when we monitored them.

When HRV decreases it’s likely you’ll see eyes more widely open and pupils dilated. When HRV increases, you’ll see blinking and pupil constriction, said DiBiase.

Over the course of a few hours, we noted that when my rescued horse, Barry, was worried or surprised by a stimulus, his HRV decreased. It took minutes for his HRV to bounce back from a lower reading.

Barry’s HRV went down and his HR went up when West asked him to back up with his hands around Barry’s head.

We observed different HRV findings with my mustang, Bug:

On a walk down the road, Bug noticed the sudden appearance of a man racing on a quad. Within a second, his HRV dropped from 80 to 40. In another few seconds, it bounced back to 80.

- Does this mean the young gelding has an innate ability to self-regulate and deal with stressors?

- Is Barry less able to self-regulate and “get over” whatever he’s stressed by?

Maybe.

Some additional notes:

- As Dr. Andrew Flatt has found with his HRV work with human athletes, HRV monitoring may be most effective when used over weeks and months, not in the moment.

- Racetrack veterinarian Dr. Christine Ross identified 13 at-risk horses by virtue of their low HRV scores over several weeks. Sure enough, 12 were injured or became ill in the subsequent months. The study has not been published, but Ross is working on a larger follow-up study to determine if HRV numbers correlate to a horse’s susceptibility to injury or illness.

- Dr. Ann Baldwin of the University of Arizona has found increased HRV values in humans when working with horses in an equine facilitated therapy setting. She is studying whether physiological information can be exchanged between horse and human (like the correlation of HR and HRV readings of paired horses and humans). Learn more here.

- This study found that behavior and compliance to a task did not correlate to physiological stress Researchers measured heart rate and heart rate variability, among other factors. Their findings may support the idea that horses can both comply and appear stoic while still being stressed.

Temple Grandin at the BHPS

Years ago, Dr. Temple Grandin labeled curiosity and novelty as key factors in working positively with livestock. HRV research confirms this: when animals investigate something new, their heart rate may increase, but so does their heart rate variability. Watch her BHPS presentation here.

There’s no doubt HRV monitors have the potential to be powerful tools for measuring physiological stress. If you do use one, try to keep your trials simple: how does HR and HRV change when your horse is being groomed? Can you correlate this with pinned ears, jaw tightness or, on the contrary, loose lips and blinking?

Hearts are not metronomes and brains are not blocks of simple dials and switches. HRV monitoring may become a handy tool in our horsemanship toolbox, but be wary of over-interpreting and oversimplifying its numbers. Your keen observation of a soft eye, steady breathing, and relaxed jaw (licking and chewing), may be more reliable. And infinitely more handy.

I encourage readers to check out the Heart Math Reserach. We are looking at ways to incorporate Heart Math into our work at UP THERE, LLC. 🙂

Wow, another great article that highlights what we know and what we don’s about the nervous systems of both horses and humans. I love this site! I have not found a better place to find evidenced-based information with real references! In other word, truly scientifically informed. Thanks so much for your ability to make the complex, simple while keeping the “simple,” SIMPLE..SO much confusion today comes from making simple concepts WAY more difficult than need be, blocking the opportunity for intuitive learning and getting it right to begin with.

I look forward to the articles!