Don’t mistake grazing for zoning out. Horses are still very much alert.

Horses – like zebras, deer, and other large prey animals foraging mostly on grass – have a head that’s perfect for what they’ve been doing for millennia: grazing in mostly open spaces and steering clear of predators.

Despite the perceived calmness and neurological homeostasis in the act of grazing, the horse’s nervous system, fueled by sensory input, is always on some level of alertness. Its senses continually assess and monitor the environment.

The size, placement, and functionality of their eyes, ears, mouth, whiskers, and nostrils are essential to who and what horses are. When you mess with horses’ features through training, care, and management, you unwittingly may cultivate stress or unhealthy situations.

A simple observation of pasture grazing can help us appreciate horses’ beautiful, long-faced design:

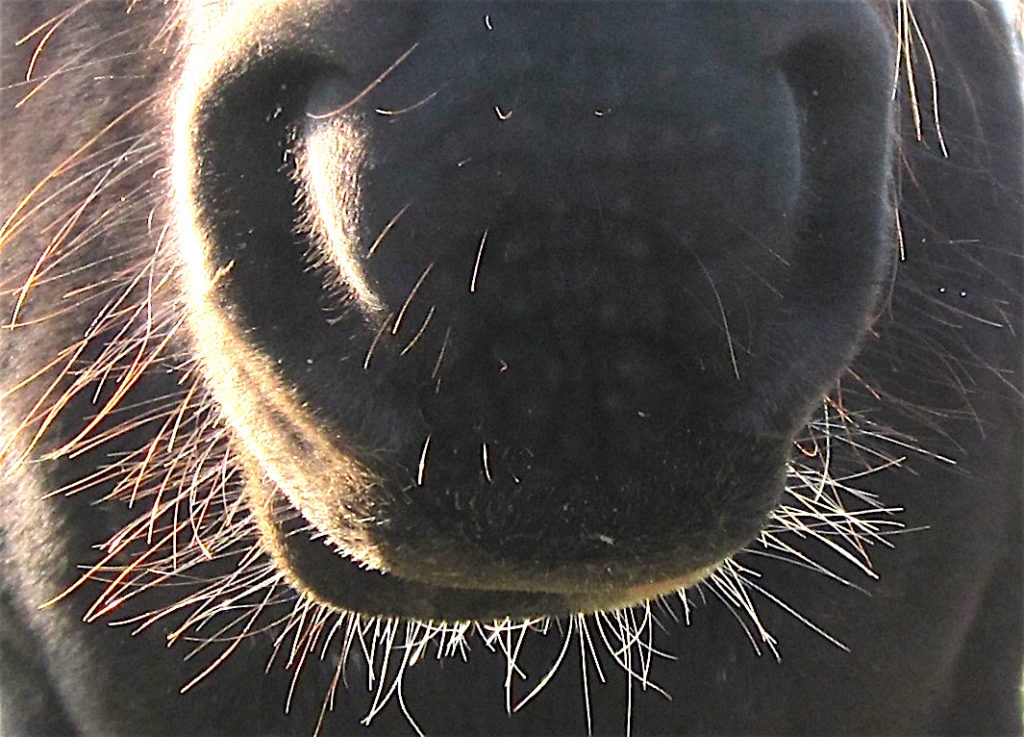

The whiskers (better known as vibrissae which have individual nerves to sense forage, novel objects, other horses, etc.) and lips do most of the

Vibrissae, crucial sense organs

investigating on the ground. Not coincidentally, the vibrissae compensate for one of the horse’s blind spots. Trim the vibrissae and you eliminate horses’ crucial sense of feel. Trimming may result in injury and stress, not because trimming hurts. Without this sense, horses are robbed of feel.

The eyes of an average horse are more than 12 inches above its mouth. At first glance, you might think that a grazing horse is looking at the ground. Not so! It’s looking around, scanning for predators or for changes in its environment (like other horses’ movement).

Here’s an equine optics primer, from The Mind of the Horse, by Michel-Antoine Leblanc:

- Horses have the largest eyes of all land mammals. Their eyes are about eight times bigger than human eyes.

- They have a large field of vision of about 330 degrees with two small blind spots – right in front of their nose and directly behind them. The horse will check the blind spots by moving its head.

- Given the visual streak of their eye structure, they see in an ultra-panoramic format. If we had an extra pair of eyes positioned near our ears, we’d have that, too

- Panoramic perspective, limited color spectrum, and excellent night vision typify equine vision

Night vision? Horses got that!

.

Academic research and empirical evidence suggest restraining horses’ heads with rein pressure or by mechanical means (martingales or tie-downs) is precisely the wrong thing to do when encountering tricky footing or obstacles.

The nostrils and horses’ sense of smell may be its most overlooked sense. Both are huge, anatomically and neurologically speaking.

Unlike the other senses, the neural pathway of a horses’ sense of smell does not travel through the thalamus (the sensory relay center that helps integrate sensations into a coherent “this is happening to me” experience).

The olfactory bulbs are situated on the underside of the brain and wired to the brain’s olfactory cortex. Horses may assess predation risk, potential mates, good or bad forage all by smell.

Letting the horse move its head will help it relax and optimize use of its senses

The ears pivot independently. Ten distinct muscles allow them to rotate 180 degrees. Horses can distinguish the direction and distance of sounds and seem to be especially attuned to sounds that could indicate possible threat or a need to move.

Many horses become noticeably more anxious when their hearing is compromised or overwhelmed, like when high winds or loud speaker announcements drown out the more crucial but mundane sounds of their environment.

Horses are motor sensory creatures. Their long-faced features have been shaped over thousands of generations by natural selection (and, to a much lesser extent through domestication) to serve them optimally.

Over time, us humans have gotten away from sensory use:

- We don’t sniff the air to determine which way it is to the beach. We read a sign or follow a phone app.

- We don’t evaluate someone’s intention through watching his approach or body movement, we use language: “What’s your intention?”

But for the horse, sensory input, maximized by its long face, rules!

I love horse science articles like this that get me to view my horse from a different perspective. They are uniquely designed creatures and we usually mess it up when we get in the way and interfere with their true nature instead of letting them use it to the best of their abilities. Ironically, it almost always turns out better for us as riders/owners when we understand this and allow them to make the most of their talents.

I Love Horse Head. This is fascinating information. Thanks soo much!!