Outside of the ranching world, entire populations of riders don’t know and don’t want to know about stockmanship. Ranchers and cowboys are considered reckless, rule-less, a bunch of Yahoos.

Outside of the ranching world, entire populations of riders don’t know and don’t want to know about stockmanship. Ranchers and cowboys are considered reckless, rule-less, a bunch of Yahoos.

In my experience, however, some of the savviest horses and riders have ranching backgrounds. These men and women can do a lot with their horses. Their horses are generally lively, athletic, talented, and ready for anything.

On a neurological level, stockmanship or working with livestock is a bit like us humans playing a team sport. Aside from the required athleticism, there’s a lot of brainwork going on.

First, consider a soccer match:

At any given second, a player will need to consider the proper power, trajectory, and spin to put on any kick, where to position herself, how fast to run, how to tackle an opponent, and so on.

Players must also consider the score, the positions and abilities of her teammates and opponents, where the ball, sidelines and end lines are, how to keep possession or gain possession of the ball, how much time is left, how much energy and skill

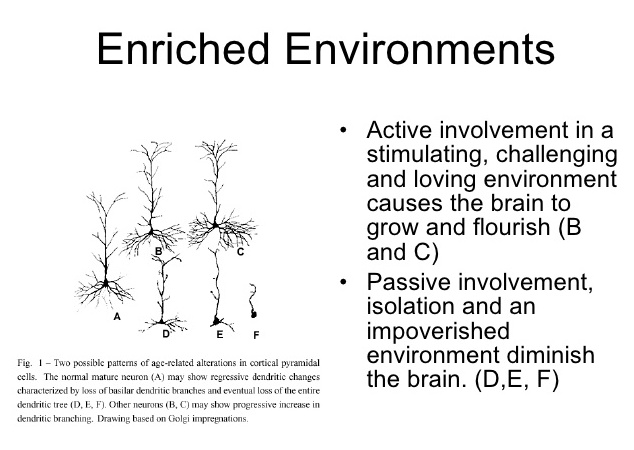

More challenges and more stimuli often lead to greater brain growth

she has, the position and aptitude of the referees, etc.

No wonder sports are encouraged in school!

Research shows that in active, involved, stimulating settings, there will be more dendritic growth, ie, greater brain development.

Dr. Steve Peters (who, by the way, played football and baseball as a kid) sees cow work as excellent opportunities for improving one’s partnership and horsemanship. Like playing a competitive sport, cow work is the kind of environment where your talents will improve while you’re busy trying to get something accomplished.

Peters writes:

Cow work can offer up the perfect learning opportunity through the nucleus accumbens (Read more about the nucleus accumbens here.) whereby the horse is constantly figuring out solutions to what it is seeing. The horse gets to learn like it learns in nature, where the scene is often the variable but also has patterns.

Moving cattle across the Mancos River

There are also many different tasks and different speed changes:

- Opening, closing, moving through gates with purpose.

- Speeding up to turn back a calf that bolts from the group

- Heading out to the herd at a fast trot, for example, is more meaningful in this setting than the endless and comparatively meaningless walk, trot, canter transitions in an arena.

Cow work is also an ever-changing task that evolves and is based on numerous variables (weather, emotional state of cattle, terrain, obstacles, and on and on).

We know that having a horse have to search for an answer can create the biggest dopamine hits. There is ample opportunity for setting up this learning scenario with cow work. With the many different tasks (crossing streams, opening gates, leading, driving, and working through lots of gait transitions) there is often less confusion about what we’re asking because the horse sees why it needs to do something. If a cow bolts, the horse understands the need to gallop.

Moving a bull across water in a steep ravine

There are also different smells and noises to learn, especially during something like a day of branding. This huge amount of sensory input can create lots of synaptic brain firing. Some stockmanship components also draw off the horse’s natural behavior. For example, horses have a natural curiosity and are drawn by movement.

Amy Skinner incorporates cow work in her young horse training. She writes:

For the horse:

Cow work helps the horse learn how to get straight. It helps it learn to stop and turn on his hind end effectively because it has a reason for that movement. They can become lighter and more responsive to aids when the work is purposeful.

It’s good exposure and helps them gain confidence because they are moving something else.

For the rider:

It helps develop situational awareness, spatial awareness, and recognition of cause and effect with cues and movements.

I think it helps teach a lot about feel because riders have to move the cow off of feel. It can teach you how to push a cow, when to back off a cow, etc. Teaching riders about cow work can help with timing and help riders understand why movements – stopping, side-passing, turning, backing – are so important. If horse and rider are not in the habit of processing those moves quickly and crisply, they’ll lose the cow.

At a branding

The rider can get a sense of confidence, too, because it provides a partnership where the pair can accomplish something together.

Whit Hibbard, author of the Stockmanship Journal has written extensively on low-stress livestock handling (LSLH) and about the value and logic behind these methods. He confirmed my observation of good ranch work as quiet, thoughtful, smart, and efficient. Not a lot of Yahoo-ing.

Success, he writes, can often be as easy as adjusting your attitude and being more mindful of animals’ behaviors and reactions. Sounds like something we recreational riders talk about a lot, doesn’t it?

Hibbard writes here about Bud Williams, the pioneer of LSLH:

As Bud advised, “The better you work animals the better they’ll work for you the next time you work with them.” …People need to realize that every time we’re around our animals we teach them to be either easier or harder to work, we teach them something either good or bad, and if we want really manageable cattle we need to work with them.