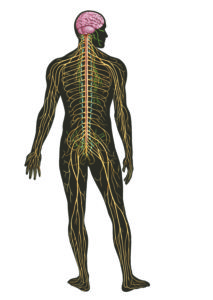

Despite mammoth differences between horses and humans, we share some similarities in the very basic development and composition of our nervous systems. We both have autonomic nervous systems (ANS), the largely involuntary regulators of our organs, muscles, glands, etc.. The parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems are the chief elements of ANS.

Despite mammoth differences between horses and humans, we share some similarities in the very basic development and composition of our nervous systems. We both have autonomic nervous systems (ANS), the largely involuntary regulators of our organs, muscles, glands, etc.. The parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems are the chief elements of ANS.

Parasympathetic and Sympathetic? Huh?

The sympathetic nervous system is what we see in Flight, Fight or Freeze situations. Let’s consider two scenarios:

Outing A:

You’re out for a pleasant ride on a nice, sunny day. Suddenly, an angry bear appears in your path. The sympathetic nervous system is called into action (for both you and your horse). It uses energy.

Your blood pressure increases.

Your blood pressure increases.

Your heart beats faster.

Digestion slows down.

Y’all beat feet!

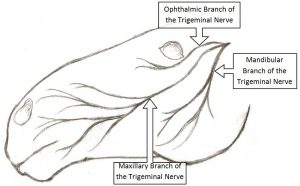

When a horse has a sympathetic nervous system response, we see the whites of his eyes. His muscles tense. His nostrils flare. Some of that is linked to the tensing of the trigeminal nerve which runs over the eye, down the face to the jaw. The trigeminal nerve also helps explain why you will see these signs (white eyes, tight jaw and lips) clustered.

Outing B:

Illustration of the trigeminal nerve. Courtesy of the Paulick Report

You’re out for a pleasant ride on a nice, sunny day. This time, however, you decide to relax, hobble your horse, and chill for a bit. There is no angry bear. You and your horse hang out in a meadow. He grazes while you read and ponder life.

Now is the time for the parasympathetic nervous system to show its colors and save energy:

Your blood pressure decreases.

Your heart beats slower.

Digestion moves.

The parasympathetic nervous system is exhibited in Rest and Digest situations. When a horse has a parasympathetic response, he licks his lips and, even if there is nothing in his mouth but saliva, he chews. He might blink and cock one of his legs.

When looking at these two trail riding episodes, we can also examine our differences. Here is where the horse’s lack of frontal lobe might actually put him in a better spot:

— You, the rider, may come away from the Angry Bear experience with nightmares and baggage. Every time you return to that spot, hear a twig snap, see a picture of a bear, talk about bear encounters, or smell huckleberries, you freak.

In studies of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder patients, chemical etchings on the brain can have the effect of turning traumatic experiences into Super Memories.

Of course, it’s also possible that you use your reasoning (frontal lobe stuff) to overcome whatever reactive responses you may have.

If the horse has enough good experiences associated with that meadow and with you aboard, he will likely override or look past this exciting episode (especially if no harm came to him). Such is life without a frontal lobe. As Yogi Berra might say, If the world becomes good, the world becomes good. Alternatively, the horse may indeed retain his fearful reaction for some time. Read about this horse who took time, attention, and body work to uncover its long-held reaction, as told by Jim Masterson.

After Outing B, the rider may come away from the experience by attaching the meadow, the smells, the book, the horse all into one fond, romantic recollection. Rose-colored glasses are frontal lobe stuff. The horse, on the other hand, may recall that he got to eat at that meadow.

After Outing B, the rider may come away from the experience by attaching the meadow, the smells, the book, the horse all into one fond, romantic recollection. Rose-colored glasses are frontal lobe stuff. The horse, on the other hand, may recall that he got to eat at that meadow.

An interesting thought. Given the locations of the trigeminal nerve network, I am wondering if aging horse dental issues might negatively impact behavior.