There’s a reason colt-starting competitions rarely feature rescued horses. It’s the same reason contractors would rather tear down a house instead of restoring it.

What’s under the surface can wreak havoc on your wallet, your skills, your patience, and even your equipment and facilities.

Troubled horses – those rescued or with stressful, less than idyllic backgrounds – have neurological baggage that can take years to unpack.

Troubled horses – those rescued or with stressful, less than idyllic backgrounds – have neurological baggage that can take years to unpack.

As owners and riders, it’s our responsibility to be conscientious of these past traumas and of the monumental, often daily challenges faced by these horses. The better we understand their baggage, the better chance we have at creating positive change.

Here’s the HorseHead perspective.

How situations become lasting traumatic etchings in the horse’s brain:

The horse’s brain is exceptional at alerting to threats. Being a sensory-motor creature, they have a “false positive bias.” Specific stimuli are considered threats unless proven otherwise. Run first, think later.

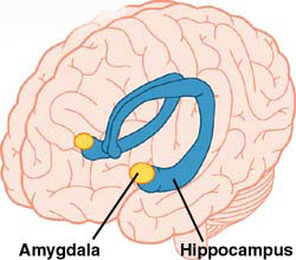

Certain noises, smells, and movements send electrochemical impulses through sensory neurons that activate the brain’s

alarm system (the hypothalamus and amygdala) resulting in a sympathetic fight-or-flight response.

If the situation or stimuli is life-threatening or is perceived as life-threatening, the trauma can be etched into memory permanently. That is, over-activation of the amygdala can create changes in the hippocampus. These brain structures are actually adjacent to one another, which makes it even easier to appreciate how emotions can impact memories.

Read more about the amygdala route in the brain here.

In humans, trauma can create Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, a condition that may include experiencing flashbacks. It’s extremely difficult to purge the flashbacks, fear associations, and bad memories.

Similarly, horses lose the ability to discriminate between past and present experiences, or, to interpret environmental contexts correctly. Their neural circuits trigger extreme stress responses when encountering situations that only remotely resemble the initial trauma.

Unfortunately, rescued horses may be limited in their ability to recover or to live a normal life. Extinguishing post-traumatic fears will rely on neural plasticity or the brain’s ability to make new neural connections.

Consider a horse with a history of trailer-related trauma: Trailer memories are neurological super highways in the horse’s brain. Recovery and rehabilitation will mean laying down one small positive neural pathway on top of another. It takes time and commitment to provide scores of positive experiences around preexisting pathways. As Martin Black has said, it may take hundreds of good experiences to compete with just one previous trauma.

Consider a horse with a history of trailer-related trauma: Trailer memories are neurological super highways in the horse’s brain. Recovery and rehabilitation will mean laying down one small positive neural pathway on top of another. It takes time and commitment to provide scores of positive experiences around preexisting pathways. As Martin Black has said, it may take hundreds of good experiences to compete with just one previous trauma.

Read about Deep Practice here.

Downregulation

Rescued horses’ nervous systems may have become up-regulated by their trauma. In other words, they are hyped up and it takes very little to send and keep them in a sympathetic state. They may panic and fight more readily than other horses.

When trainers and owners apply more, undue pressure, they keep these horses in an overly-aroused state. Discomfort like this only exacerbates troubled behavior. Read more about downregulation here.

What about Mustangs?

Mustangs may not have experienced overt trauma, but their lack of positive human contact means they present similar

Trainer West Taylor works with mustang

challenges. It may be extremely difficult to help these horses find relaxation. Accomplished trainers will look for tiny windows of opportunity to downregulate a mustang’s nervous system. Results come from observing minute shifts in comfort and rewarding them with release of pressure.

Read our collection of mustang training and progress note.

What about Learned Helplessness?

Learned helplessness is another consequence of neglect or abuse. It happens when animals are put in inescapably stressful environments. Regardless of their attempts, they can find no relief. These unfortunate scenarios result in depressed behavior. On a brain level, the neurochemical, serotonin, is impacted. Serotonin is related to mood balance. The key feature of learned helplessness is the transference of this shut-down behavior to all situations.

To breakthrough this passive listlessness, one has to reestablish exploratory behavior and curiosity and the accompanying  dopamine reinforcement. In other words, the trainer needs to show the horse that it has control over its environment and encourage it to engage with the environment. Minute victories and small, multiple successes can help redevelop an internal locus of control for the horse. That internal locus of control? It’s what we call confidence.

dopamine reinforcement. In other words, the trainer needs to show the horse that it has control over its environment and encourage it to engage with the environment. Minute victories and small, multiple successes can help redevelop an internal locus of control for the horse. That internal locus of control? It’s what we call confidence.

good job explaining a range of different issues. Why just loving the horse isn’t enough (know you didn’t mention that but a common misconception in “rescuing” a horse). I cringe everytime a person who knows nothing about horses “rescues” one. & to quote someone who knew a bit more than I “I’ve never seen it take more than 10 years.”

Thank you so much!!! I am rehabbing a 13 year old Standardbred off track former broodmare. She had so much baggage and now, after a setback followed by a year of only at liberty work, last night SHE ASKED for the saddle pad and saddle.

No!!!!!!!!!!

On rescued horses. Work with 1,000 rescued horses and you’ll have 1,000 different experiences. Some may have been physically abused. Some were generally well cared for, but perhaps the owner died or had a financial setback. Work with 1,000 horses you buy from horse dealers, and you’ll also have 1,000 different experiences. Some of those horses may have been abused and some may have been psychologically-scarred by well meaning, but clueless owners.

There are no studies cited in this post that demonstrate that rescued horses are tougher to work with that non-rescues. The discussion of brain anatomy is not validated by population studies — peer reviewed or not.

The same goes for mustangs. If you’re talking about a mustang that was captured as an older stallion and held at a BLM facility for years, that’s different from a mustang yearling captured off the range and put into ground training by a competent trainer.

Horses, like people, are individuals. Whenever you buy or adopt a horse, you should check the claims of the seller. A big advantage of rescued horses is that most rescues are completely honest about what they know about the horse’s background. A rescue I work with, Bluebonnet Equine Humane Society in Texas, provides adopters with a 30 return policy — your adoption fee is refunded if the horse doesn’t work out for you. How many horse dealers offer that?

C’mon now!

Good points . Perhaps the article should have been more specific in regards to those horses with histories of abuse or traumatic experience. You are right in that not every horse that has been subject to abuse is going to develop a PTSD like syndrome. A horse that is “rescued” due to the fact that its previous owner has passed away is probably not going to have had similar experience to a horse that has been abused and been seized by the state.

I think the point of the article had more to do with what happens once a horse becomes a rehabilitation project. I would also agree that a mustang yearling is probably going to be different in their responses than an adult who may have a high level of excitability and self preservation. Thanks for your comments

Excellent comment!

I’m an equine behaviorist (with a doctorate and peer-reviewed publications as well as popular press articles) and I also work with rescue horses.

It is true that there are rescue horses who cannot recover from past trauma or can only recover with a lot of time and training. HOWEVER, those horses exist outside the rescue world, too. There are competitive horses, pleasure horses, trail horses, and working horses who have been abused or misused or pushed too hard too fast. Those horses have the same problems you describe. Trauma is not limited to the rescue horse.

There are many rescue horses who come from neglect, abandonment, stray, etc. situations who make a great recovery and go on to do the exact same things non-rescue horses do. I could cite example after example – horses who are competitive trail horses, endurance horses, show horses, hunters and jumpers, dressage horses, ranch/working horses, kids/4-H horses, etc. etc. etc. who came from rescues and recovered.

You do a disservice to the horse when you lump them together. Take each horse, whether rescue or not, as it comes. Invest in good training (whether by investing the money for a professional or the time yourself) and treat the horse correctly and stop worrying about whether or not the horse came from a breeder, a show barn, or a rescue.

Jennifer, thanks for your astute comments. This article was intended to help rescuers or potential rescuers to gain some insight into problems faced by troubled horses. Indeed, many horses that come from non-rescue situations are quite troubled. That’s why the title references the ‘troubled horse’s brain.’ You’re quite right that no horse is the same as another. Thanks for contributing your thoughts.

I love this. I have a biological background and was aware of some of these brain changes that can occur due to bad past experience and be unbeknownst to us. What I like is that you don’t say that someone should not take on a rescue horse but this just helps us to be aware that there may be psychological baggage and that we should be aware that it may take much more time, effort and care than we could have imagined.

The article and comments are wonderful, thank you. I also read some of the linked articles. We have an 8 year old QH who apparently was abused by someone in the past. The person I got him from had him in a great routine…stall boarded, with some pasture time then when ridden he had arena work then maybe a trail ride, then back to the stall…he was responsive and well trained…Our horses are kept out 24/7 in a herd of 4… I found him extremely unsettled by non-routine handling. Taking a walk was very difficult…so we took a lot of them… He was nervous when if a person was on his right/off side…could not walk with someone on that side…so we did a lot of that… When being ridden he no longer has the routine he was used to so when things get too much he shuts down – goes very still – then explodes. He also gets very nervous when in ground work is asked to go near fences or anywhere escape is difficult. He will bolt through…we’ve been working on that and he is better. I haven’t ridden him in over a year…but the trainer has. I have hopes of doing so one day because he is making progress…it is taking him a long time to let go of his trauma. He is also extremely head shy. At first brushing his neck higher than the shoulder was a cause for raising his head…now you can start near the top…ears are still a problem, but we can stroke the outside most days. It took a bit of time before the extreme head shyness and other problems began to show up…I guess he was so shut down he took it all, but as that lessened he began to let us know what was scaring him. He also cross canters and I wonder if he has a physical problem that makes picking up the correct lead difficult. I found a massage therapist who is working with him now. We live in a very rural area where services are hard to find. I hope to read more articles about how to help horses with past traumas…

I read this with interest. My horse is a rehab project kind of rescue. This information is helpful to me and reaffirms the slow, steady work we are doing together. I know it will take years for his brain to adapt but I see it happening little by little. The above entry could be written about my horse – in particular, and scary for me when I rode him ( we are just starting to get back on him)

‘when things get too much he shuts down – goes very still – then explodes’

This kind of behavior is scary for the handler/ rider too and I have needed to do my own work on my nerves and anxiousness to be able to keep myself calm and focused too when he starts to build up. I try never to let him get to that point but sometimes it happens fast – at least now we recover more quickly and fall back on the calming work we have built up in his mind/body.

Thanks for this affirming and interesting information. Best, Liz