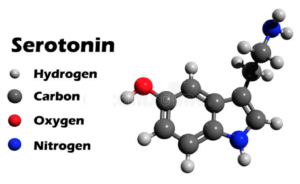

Serotonin molecule

As a follow-up to the HorseHead article on serotonin, we visited with several renowned trainers for their observations and experiences around learning moments likely influenced by serotonin.

Keep this comment from Dr. Peters in mind as you read of their experiences: “Research on the effect of serotonin on learning seems to be showing that perhaps the key is not just searching out knowledge and getting a reward but being “safe” in the nervous system and having enough time in that “no stimulus” state to cement what they are actually learning and to make associations (i.e., long dwell times). Helping the horse to feel safe and find a place of internal security may play a huge role in how well they learn and the rate at which they learn.”

We spoke with Martin Black, horseman and co-author with Dr. Steve Peters of Evidence-Based Horsemanship. He recalled that when he was younger, he might have worked more quickly when colt starting. He realized, though, that there was no gain to be had with speed. It’s an especially hard lesson for horsemen to learn, especially if they are “warriors,” men used to muscling through challenges.

Black writes:

Martin Black. Photo courtesy of Eclectic Horseman

Take for instance a horse who’s stressed, whether in cow work or if it is being worked quickly while doing something, or perhaps with a colt in training, unsure and on high alert…After they experience those situations with positive outcomes, that’s when I’d wait for ten minutes rather than two minutes.

You can give the horse more time. It doesn’t cost anything. There’s no benefit to cutting it short. Extra time is well worth it.

I don’t like to give exact rules or anything. No two circumstances are going to be the same. But I’d rather sit there and twiddle my thumbs and have my horse rethink the experience they just had.

The quickest way to get to a good point is not with a short cut. If your time is too valuable, you shouldn’t be out there with horses anyway. For years, I’ve seen folks muscle up and keep going, especially warriors like myself.

My wrangler, Mike, and I have been calling serotonin the Drug of the Month. For us, it’s what creates emotional balance.

We apply pressure and then we see a release and subsequent licking and chewing.

But, now, how am I seeing emotional balance?

It’s the softening, the head and neck relaxing. They often turn and look back at the hip.

West Taylor

I think serotonin is there when the horse is mentally engaging. It’s like the horse is doing a playback or review of what happened and finding a mental balance after coming out of a fight-or-flight situation…Whereas when dopamine (licking and chewing) is onboard, there still may be some tenseness.

The next state that we watch for is when we allow the horse to seek mental safety…their alarm system is almost completely turned down. They seem to say, “Nothing is happening next.” It’s not, “now what?”

Dwell time is super valuable. It may be involved in a 30-minute training experience or over the course of days or even months. I’ve left horses with good training experiences and after six months, I can get back quickly to where we left off.

Initial work with young mare

I started working with a nice, three year-old Welsh-cross dressage prospect last summer. She was easily agitated, bothered, and crooked. Her crookedness was due to a mental kink, not any physical defect: when she became bothered by my teaching something new and something she didn’t understand, she’d become crooked and unbalanced (throwing a shoulder or hip out) and use her shoulders as an anchor to buck or bolt. She would explode due to frustration, just from a simple request to turn left or stop straight.

My temptation would be to fight with her and make her do as asked. From a human point of view, they were simple requests. But when she became agitated, I nonetheless backed off. She took some time to relax, and she worked on the edge of trouble for a good three months.

- When a horse walked by the arena, she lost focus and panicked.

- When the sheep near the arena moved along for their daily breakfast, she would become crooked and bolt.

Anytime she got upset, I backed off and worked on something simpler and wait for relaxation. I’d look for her to become softer and easier to direct. I’d watch for relaxation, more rhythmic breathing, and a more natural headset.

Anytime she got upset, I backed off and worked on something simpler and wait for relaxation. I’d look for her to become softer and easier to direct. I’d watch for relaxation, more rhythmic breathing, and a more natural headset.

Over time, she became relaxed. I’d bring an extra horse into the arena while tasking her with a job. I took her off the farm and rode her in groups. After about a month of these “extras,” I took her to her first show.

It was an enormous, rated show. I was a little worried about her being overwhelmed. But she walked calmly past whizzing golf carts, kids crying, horses screaming, dogs barking, and handlers cracking whips. My husband groomed her with the lead rope over her neck in front of the warm-up ring. She was still and quiet.

When I went into our materiale class (a class where young horses ride together to show dressage-prospect), she was the most relaxed and quiet of the group.

I attribute our success to hundreds of hours of simple, quiet work, and my backing off anytime she was worried.

I attribute our success to hundreds of hours of simple, quiet work, and my backing off anytime she was worried.

It’s a method I wasn’t sold on previously. Many would say she needed to be desensitized, to learn to deal with chaos by shutting it out. But at the show, this horse was able to be aware of every detail around her and yet not be bothered. She didn’t ignore things; she just wasn’t concerned. She had plenty of life available for her class and remained sensitive enough to respond to my leg and hand in the ring without extra whip or spur help.

Ray Hunt said, “You leave the life in, take the fear out.” I was proud to be sitting on a horse with plenty of life and lots of trust.

Amy Skinner shows the now calm, relaxed young mare

How lovely and so true! Maybe this can someday be the norm for all folks in dealing with their horses. Would love to see this be the commonplace plan when working with any horse.

What I find interesting in many of the HorseHead features are scientific explanations for the behaviors and responses that we experience out in the field. Those in turn can provide validation for more effective and less stressful training approaches. Particularly with some horses, providing some “soak” time when processing something new can actually turn out to be a real time saver.

From my experience I think trainers need to view serotonin in the context of the other chemical feedback mechanisms. Serotonin seems to play a very beneficial role with horses that have previously been pressured too hard and where too much going on appears to produce reduced concentration, confidence or stress. I have to say, however, that with quick thinkers (we call them dopamine addicts) that have busy minds and get bored easily, the chemical feedback produced by problem solving often is the best propellant. My point is that we need to understand the horse we are working with and increased awareness of relevant neuroscience helps us be more accurate in those assessments.

Also, all too often we observe people mindlessly pressuring horses in training. The endorphins released from running might be great if the objective is to barrel race or ride a Pony Express re-ride leg. But when used in the wrong context, running a horse that one wants to be calm and train, such as chasing it about in a round pen, can simply reward the horse for running away from pressure. Not saying that sometimes a horse won’t benefit from running. As trainers we just need to have a legitimate purpose for it and understand the potential effects.

I also want to mention soak time for trainers. We sometimes deal with difficult and even dangerously reactive former range horses. In some of those projects we may have two or more people team up during various desensitizing and training elements. When a horse struggles and finally gets it, we’ll often just stand around in the corral with the horse, making small talk. It’s kind of a social, herd thing. The horse gets to soak and so do we, often inadvertently resulting in some clarity.

As an expert in reading human body language, I’m certain that the horse reads our “chilling out.” It’s not unheard of for a horse that absolutely refused to be touched and would run away if a human entered the pen would, following some “soak” time, quietly walk up and bump one of us with his nose as if to ask, “Are we going to do something else?” Or maybe the horse is just expressing, “It’s OK. I got it.” We need to get as good at reading them as they are of us.

That’s a quick nutshell comment. Obviously there is a lot more to it. Keep up with the great articles!

Absolutely. Willis’ comment above reminds me of a quote Tom Dorrance is credited with, “Going slow is the fastest way to get there.”

Congratulations to Amy on making life so much better for the insecure mare. Developing a feel that allows us to back off (reward) immediately prior to when/where the horse gets uncomfortable, rather than waiting until cortisol is on the rise, is also an effective way to help the horse learn to stay endorphinzed in previously stressful situations.

For trainers who also work with people, it’s useful to know that this mindset helps the human student retain positive information.

Thanks to all of you for all you do to make life better for horses.

Thanks Cheryl!