Jolene appears at ease during this lay down by West Taylor

Talking about laying down a horse can be like discussing presidential politics. Some steer clear altogether. Some engage passionately. Many are interested, but wary. Beliefs and traditions run rampant, but science takes a backseat.

We’re here to change that with an examination of the brain science surrounding the lay down. Some images are of West Taylor, a Best Horse Practices Summit presenter and a trainer who works mostly with wild horses at his Wild West Mustang Ranch in Fremont, Utah.

Before we dive in, let’s be clear:

- This practice should be performed by experienced hands, in a safe environment, with as little stress as possible inflicted on the horse. Ideally, it is a quiet, drama-free affair.

- Neurologically speaking, horses are often reported to have made a significant shift after a lay down. In the wrong hands, this shift may not be positive.

- There is a lot we don’t know. Horsemen and women should consider the best interests of the horse, not only in the immediacy of the lay down, but its possible ramifications afterwards.

The Science:

Image courtesy of Neuroscientifically Challenged

First, it’s important to know that there may be more nuance to the “Flight or Fight” response of the sympathetic nervous system when a threat or stress is imposed or perceived as imminent. The Polyvagal Theory proposes adding “Freeze” to the possible reactions.

In this state, heart rate, respiration, and blood pressure all decrease. Limbs may be limp. As far as brain chemistry goes, we believe it is the opposite of the physiological responses involved in flight of fight. It’s also the opposite of the stoicism we may see with learned helplessness, even though to an uninformed observer, it may look comparable. In learned helplessness or other behaviors of stressed stillness, cortisol levels and other stress indices (heart rate, etc.) are elevated. Not so with a proper lay down.

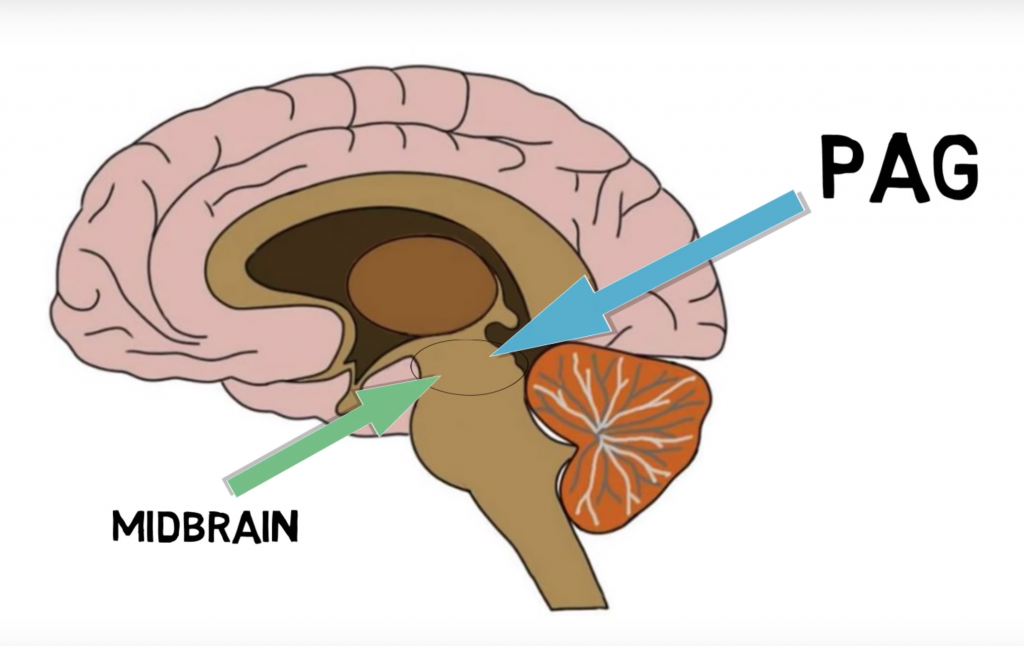

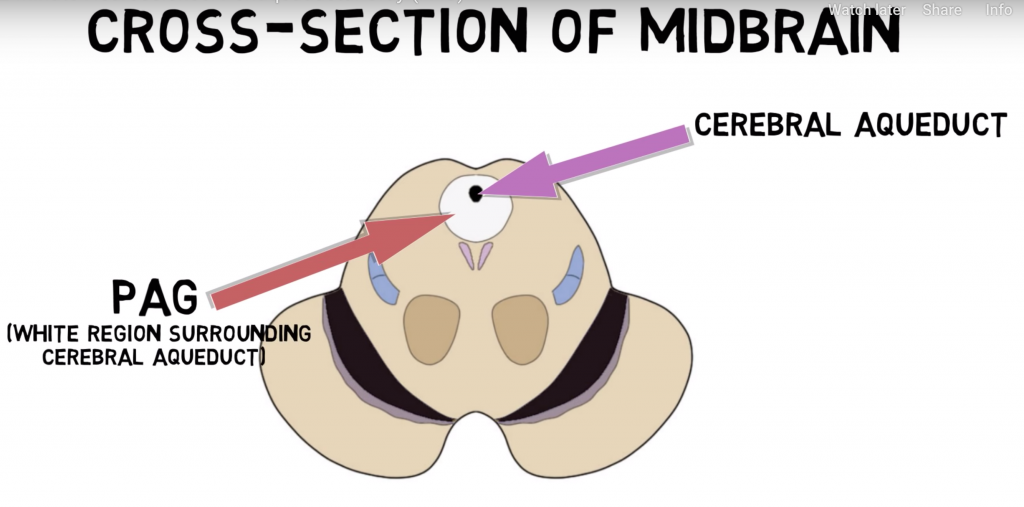

Second, while what goes on in the horse’s brain is purely speculative at this time, we believe that activity in the mid-brain region of the Periaqueductal Gray Matter (PAG) is essential to grasping what’s happening neurologically during a lay down.

The PAG, located in the brain stem, modulates pain circuitry from the brain to the spinal cord and is known to inhibit pain. It has enkephalin-producing cells [Enkephalins are likely neurotransmitters with potent opiate-like effects and are classified as endorphins.]

Image courtesy of Neuroscientifically Challenged

Of course, self-preservation is not just about dealing with injury. It’s also about dealing with the possibility of injury or the perception of possible injury. In other words, you don’t have to experience actual pain for the brain to activate a stress-reducing chemical change. It also helps us appreciate how the PAG is believed to be involved the placebo phenomenon.

The PAG has the ability to block pain signals from reaching the brain and can also release endogenous opioids in its areas that are rich in opioid receptors.

Taylor points out Jolene’s slow breathing.

In horses, we believe the PAG may be involved in providing a rush of pain-blocking, opiate-rich neurochemicals in stressed and compromised situations. Consider prey animals that have been downed by a predator and are on the verge of being killed and eaten. The suffering they feel would be alleviated by this neurochemical change. It would also explain what we see as a “giving in” to their situation. Evolutionarily speaking, “giving in” may have benefitted prey animals in a way that may have increased the likelihood that they would somehow survive this life-threatening scenario.

Trainers also see a “giving in” when their horses have been laid down. After a certain point, they do not struggle. Indeed, horses may stay down for several minutes even when they would be free to leave. Some even nap.

It may be that the analgesic impact of the PAG has the effect of rose-coloring the experience. It often appears that the horse is dreamy and at peace once laid down. Many trainers attest that huge strides can be made, especially with difficult horses (like wild horses or older, untrained horses) after lay downs.

What would the horse say about the experience? We don’t know.

Learn more about the PAG here.

Watch this 2-minute video on the PAG here.

Interested in more horse brain science, check out Horse Head: Brain Science & Other Insights.

very interesting

Very interesting ,horse looks very relaxed

I’ve spoken to TJ Cliborn about this and he said Temple Granding is looking into this as well. Nonetheless, it’s tricky. (Don’t rip my head off. Not saying it’s good or bad, just tricky.)

We agree, Kerry!

My mule was laid down for dis respect by a trainer at 3 years. She never recovered.

Before she was friendly and trusting,

Afterwards and now she trusts no-one, and is untrainable. It broke my heart and hers.

This form of training is not something to be messed with.

If you want to lay down an animal !!! may I suggest you first ask why.

The only healing process where the animal chooses to relax into rem sleep is with James French of Trust Technique

I have witnessed the laying down by several trainers in the Mustang makeover events. Most of it looks like showboating for the audience’s applause approval that they got the horse to ‘surrender’. I doubt very much that the horse learned anything. As when the horse is released from the catatonic state it reverts back into the same behaviors. I don’t have any scientific answers here at all. Just observations. Albeit there are different laying down methods and different horses and circumstances, I am just very skeptical until I see any science in it.

Thanks for your comment. We agree that there are as many methods and resulting outcomes as there are trainers. Those that do lay downs in the way described here may be genuinely doing it with the horses’ best interested in mind, but, yes, there are others as you described.

Great article.