Years ago, I defined Feel on BestHorsePractices as an intense awareness of action and reaction. Feel is knowing how your thoughts, behaviors, and movements impact your horse. It’s an ability to anticipate and influence your horses’ actions and behaviors.

Years ago, I defined Feel on BestHorsePractices as an intense awareness of action and reaction. Feel is knowing how your thoughts, behaviors, and movements impact your horse. It’s an ability to anticipate and influence your horses’ actions and behaviors.

But what does that look like on a neurological level?

We can turn to neurologists studying baseball players to help us decipher the brain science behind horse-human interactions.

To understand it, we must first consider how one distinguishes different kinds of movement. The Motor System Hierarchy identifies increasing levels of brain involvement.

Motor System Hierarchy:

At the bottom and most basic level, there are reflexes:

- a twitch

- a lower leg kick that happens when a doctor taps your knee just so

- an instant hand-on-hot-stove withdrawal

- catching yourself from stumbling and falling on your face

Reflexes involve the brain stem and spinal cord, primal parts of the brain that we share with all animals.

At the mid-level of the Motor System Hierarchy, there are simple or stereotypical movements. These are procedural movements we do all the time. Not a lot of higher-level brain power is required to walk, open a door, or even ride, after you’ve practiced. The brain areas engaged here are the motor cortex and cerebellum. We are best at these mid-level movements if we are fit and if we practice.

The highest level of movement involves the neocortex and the basal ganglia, more evolved regions of the brain. Activations from these areas involve intentional movements of self-expression and complexity. When the neocortex and basal ganglia are involved, says Dr. Peggy Mason of the University of Chicago, the movement becomes a “meaningful action.”

The highest level of movement involves the neocortex and the basal ganglia, more evolved regions of the brain. Activations from these areas involve intentional movements of self-expression and complexity. When the neocortex and basal ganglia are involved, says Dr. Peggy Mason of the University of Chicago, the movement becomes a “meaningful action.”

Riders engage all levels of this hierarchy and the really good riders are especially quick at the higher-level brain processing.

How can research on baseball players inform our horsemanship?

It’s tempting to assume that players with the quickest reflexes are the best hitters. After all, most pitches are delivered in the time it takes for you to read a single word. But most folks – professional ball players and the rest of us – actually have comparable reflex times. We’re all quick. Our knees all jerk the same.

Moreover, it turns out prowess at the plate doesn’t have much to do with fast-twitch muscles or physique. As Zach Schonbrun wrote in “The Performance Cortex,” two of the very best hitters contrast starklly in their physical make up: Aaron Judge of the New York Yankees is 6’7’’, 285 pounds and Jose Altuve of the Houston Astros is 5’6’’, 165 pounds.

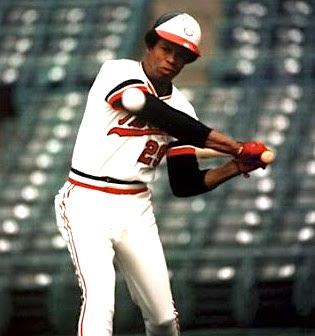

Rod Carew had superior rapid perceptual decision-making ability

So, what makes a baseball MVP?

What distinguishes a master horseman with incredible feel?

It’s the ability to process and act when they engage in those higher level movements of the neocortex. It’s called rapid perceptual decision-making. Great hitters are great not because they react quickly but because their higher-level brain processing is so fast that, in fact, they can afford to relax and wait.

Hall of Famer Rod Carew epitomizes great feel, says Dr. Steve Peters (who himself played Division I collegiate baseball):

“If you look at where the baseball is in this picture, you can appreciate just how long Carew was able to wait to decide weather to swing or not. The swing is fluid. His hands are soft. His timing and feel are impeccable. He always seemed to get the fattest part of the bat on the ball.

A non-baseball perspective can inform us of the stillness and quiet involved in rapid perceptual decision-making. Consider a cat:

Watch as it prepares to pounce. It is still, relaxed, and focused. It is taking in lots of somatic information (the movement of the mouse, the quality of the terrain, the light, the wind) and processing at lightning speed to inform a successful pounce. The successful cat has incredible feel.

The author, Schonbrun, explains that really good players produce or respond to “patterns of spatially and temporally distinct and interdependent neuron activations” in ways that are different than other people. Adds Peters: “Lesser batters get fooled. They will put the command to the brain stem and spinal cord to swing too early. Or, their processing from the neocortex will not be fast enough and they swing late or not at all. “

Quiet movements belie quick brain processing. Photo of Amy Skinner

Great players with fast processing have the luxury of not executing the movement until the last moment. They can subconsciously say, ‘wait, wait, wait,’ as they read the pitch. Players’ reflexes are pretty much all the same. For those very good players, the processing speed is much faster.

Translated to horse-rider interactions:

Sure, a lot of our work around horses involves mid- and low level movements. But feel involves taking in a vast spectrum of somatic information from visual input to proprioception to memory of past experiences. As this happens, the best riders may be uncannily quiet, still, and relaxed. It’s not unlike the batter reading a pitch or micro multitasking.

- Are my horse’s ears up?

- How light is my line?

- What did he do the last time I gave him this cue?

- Is the wind bothering him?

The best horsemen recognize the fluidity of any situation with any given horse. They take it all in and react with a decisive movement to those patterns of spatially and temporally distinct and interdependent neuron activations, cited by Schonbrun. Quiet movements belie quick brain processing.

Kate Neubert

As with Carew or the cat, the great rider’s brain is “very busy processing everything, but it’s not really thinking,” says Peters. “The rider is reading and readjusting, but he or she doesn’t have time to articulate what’s happening. There are no words for it.”

As with baseball players, great feel with horses takes practice, experience and a special awareness. From a big picture perspective, feel is the ability to be in the moment while also drawing on reams of prior experiences. If we think too much and try to bring in language and self-consciousness, we miss the moment for effective communication with our equine partner.

So, have fun out there! And be like another Hall of Famer, Yogi Berra, who said, “you can’t think and hit at the same time.”

Ah HA! Thank you. Seems like a key word could be “relaxed”.

cheers

Well, that a great article. Well said.

Love these analogies….you took a hard-to-explain topic and broke it down very well. Thanks so much!

In reviewing significant rider accidents, the events and conditions that preceded many of these accidents tended to correlate with the explanations offered in this article. Riders who rode with too much tensionappeared not to receive sufficient proprioceptive messaging from their bodies, or perhaps they produced proprioceptive overload. But regardless, the result was that they lost that intuitive connection with their mounts and failed to adjust appropriately in “real time.” Then there are riders like me who sometimes become a bit too laid back with a very trustworthy horse and occasionally find themselves trying to “catch up” to the moment when something unexpected happens such as when the horse collapses a jackrabbit tunnel. Of course alcohol or drugs can exacerbate these situations.

Especially when traveling in rough country, we try to exercise constant “soft situational awareness.” By this I mean while we are on some job or are just having an adventure, we try to maintain that intuitive connection with our mounts, and that involves consistently practicing the skills described in this article. My opinion is that this process is what some of the old timers called “unity” or “getting more with less.” Keeping this process active while maintaining situational awareness of the surrounding environment appears to not only increase the degree of rider safety, but from my observations also increases the degree of confidence of the horses being ridden. Their riders, who should be in charge, have taken the responsibility of being aware and making minor adjustments as may be appropriate.

Also there seems to be a correlation in that as riders and their mounts relax, they seem to be able to do more without becoming fatigued and uncomfortable. They are also probably a lot less stiff and sore after a hard day’s activity.

It’s one thing to say, “Relax and get in tune with your horse.” However when one begins to understand the processes that take place, it can provide a path for developing a safer and more enjoyable equestrian experience.

This all sums up to what is called “flow state” in both the casual vernacular and science literature. A place horses live in easily. Processing sensory and somatic information with less pre frontal cortex jabbering away. Love that place when I find it.

Right on. Thanks, Kerry.

A few things stood out to me –

We all have the same reflexes, but it is the ability to be calm and wait.

I notice I don’t seem to ‘think’ while I ride, tame, train. I am in the moment – and when teaching that makes it hard to put words to it tell someone else what to do and when, because the moment has passed. I’Ve been doing some online training videos, and I never feel like I’m doing it justice when I’m speaking as I work. Perhaps doing an audio voiceover afterward is a better way to communicate the subtleties of feel and timing better.

I also notice some people seem to be able to learn this feel with minimal input from me, while others just don’t seem to be able to quite get it – so can this high level of feel be taught or learned?

Anyway…a ramble of thoughts! Thank you for this post

Great comments and observations, Ellie. Thanks so much for being part of the conversation.