Editor’s Note: At HorseHead, we’re intrigued by Polyvagal Theory, a relatively new explanation of the autonomic nervous system, present in all mammals. This is an introduction to Polyvagal Theory and its application with horses and horsemanship. Please note: what follows is theory and not yet supported by evidence or peer-reviewed research.

Order Horse Head: Brain Science & Other Insights

For decades, we have considered the autonomic nervous system (ANS) as a feature of the brain stem, a primitive part of all mammalian brains. The ANS is comprised of the parasympathetic (PNS) and sympathetic nervous systems (SNS). We recognize these states when we and our horses (At this primitive and reactive level, our brains are quite similar.) are in ‘Rest & Digest’ mode (PNS) or ‘Flight or Fight’ mode (SNS).

Many model the ANS as simple PNS and SNS light switches (albeit with dimmer adjustments). We can assess our horses as they toggle between two states, relaxed or stressed.

Many model the ANS as simple PNS and SNS light switches (albeit with dimmer adjustments). We can assess our horses as they toggle between two states, relaxed or stressed.

But set aside that metaphor and make room for the more nuanced approach of Polyvagal Theory, proposed by Dr. Stephen Porges some 20 years ago. Porgas is a Distinguished University Scientist at Indiana University and founding director of the Traumatic Stress Research Consortium.

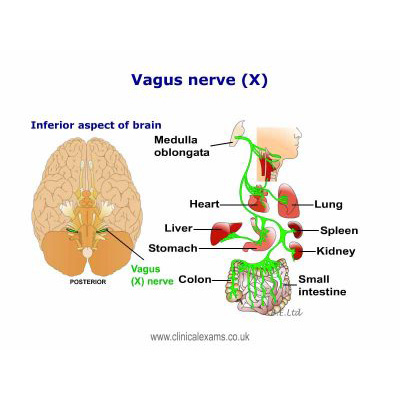

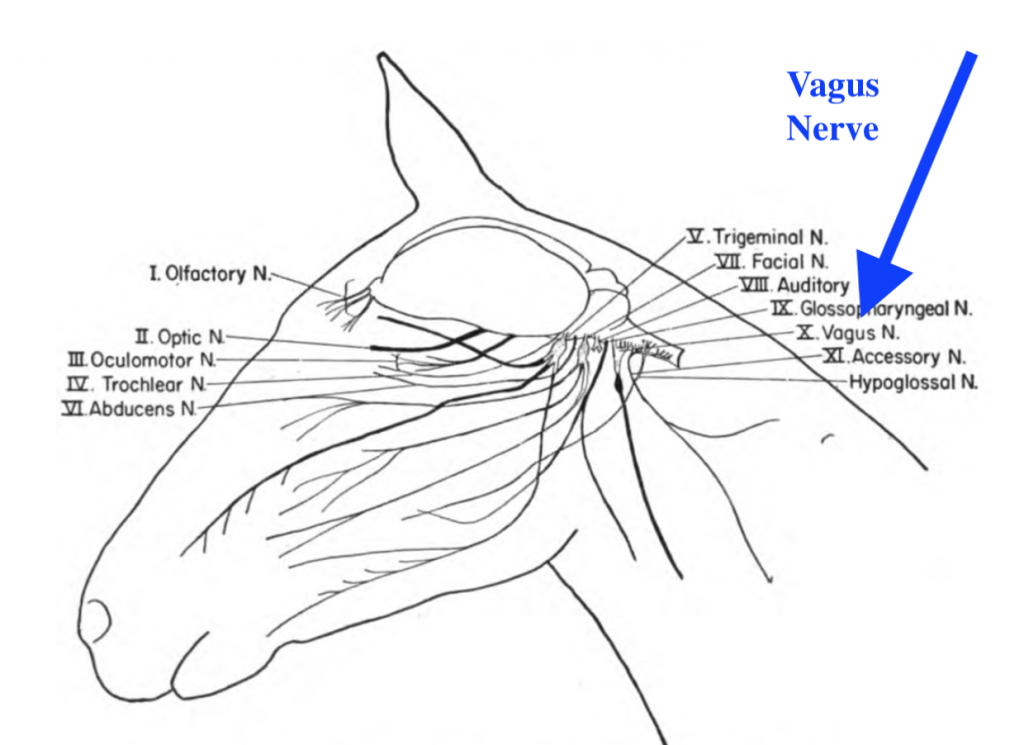

Porges championed a new interpretation of the ANS as it exists in the brain stem and expands throughout the body and brain via the vagus nerve, the 10th cranial nerve running from the head to other parts of the body and brain.

The vagus nerve is made up of three ‘complexes,’ one sympathetic and two parasympathetic parts. If you’re like me and benefit from imagery, replace those ANS light switches with three dials that move up or down perpetually as situations develop and environments change.

The dorsal vagal complex (DVC), part of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), is most primitive and activates a freeze or fold (collapse) response. Think of a brake pedal as a metaphor. When the DVC is highly activated, the brakes get slammed.

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS), as with the earlier model of the ANS, involves mobilization. But unlike the earlier model, Porgas sees any movement – play, sex, walking, as well as fight and flight – as a consequence of SNS activation. Think gas pedal as a metaphor for the SNS.

The ventral vagal complex is part of the PNS and, according to Porgas, should be thought of as the softer brake. It is the dial that “provides the brakes that tempers the SNS just enough that play is fun and does not flip into fight or flight activation….it also allows social interactions to regulate physiology and promotes health, growth and restoration,” says Porgas.

One crucial element that polyvagal theory allows for is the “freeze” that we horse folks know well, but that the traditional ANS interpretation didn’t directly address. Previously, the freeze response was considered a more conscious action. This idea has troubled researchers who knew, for instance, that rape victims were not making a conscious decision to freeze. Horses, similarly, were freezing when extremely frightened, sometimes giving the impression that they were “bomb-proof” when in fact they were ticking time bombs.

Vagus nerve involves scores of organs and muscles. Image courtesy of ClinicalExams.co.uk

Polyvagal Theory allows for what Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk (author of the outstanding book, The Body Keeps the Score) calls “a more sophisticated understanding of the biology of safety and danger, one based on the subtle interplay between the visceral experiences of our own bodies and the voices and faces of people around us…”

For the last few years, some trainers have been focusing on relationship-building with his horses with a relationship first, then training strategy. Using Polyvagal Theory has been part of that shift.

Trainers might work first and foremost on fostering a safe environment. for example. That comes from acknowledging the tiniest changes in their behavior as they interact.

Image courtesy of Quiring, D.P. (1950). Functional Anatomy of the Vertebrates.

Dr. Steve Peters, who helped with the neuroscience in my book, Horse Head: Brain Science & Other Insights:, adds:

“Think of safety as a foundation on which you ask for bigger things,” said Peters. “You can’t get anywhere without it. That’s what keeps the engagement. There is no social engagement between you and the horse if you push the gas pedal or the brake pedal too hard.”

Resources:

Sarah Schlote’s excellent article on Polyvagal Theory

Consider Polyvagal Theory and how to deal with anxiety during the pandemic. Great article here.

Squeeeee! I was super excited to see this article. Some of my work in the EFL realm is related to this. Thank you for sharing the great work Warwick and Sarah are doing together. I look forward to the day we could see the two of them presenting together at the summit!

Wonderful descriptions to help us lay-folk to understand these terms around the nervous system!