Neuroplasticity is a healthy brain’s ability to form and reform synaptic connections created through gazillions of moments. Every being – from a lab mouse to a horse to a human – is unique because of these moments and subsequent memories They are experiences stored and recalled.

Neuroplasticity is a healthy brain’s ability to form and reform synaptic connections created through gazillions of moments. Every being – from a lab mouse to a horse to a human – is unique because of these moments and subsequent memories They are experiences stored and recalled.

Our capacity to maximize our neuroplasticity – to continue to learn, develop, and sharpen our skills – depends on how much effort we dedicate to the task and, as researchers are finding, what kind of effort we put to the task.

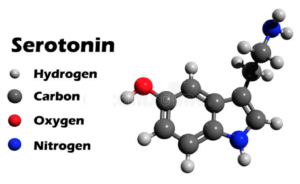

When it comes to facilitating our horses’ learning, new research is highlighting the importance of one brain chemical in the process: Serotonin.

Like dopamine, serotonin is a widely impactful neurochemical. We’re most familiar with its connection to mood. Anti-depressant medications, for instance, makes more serotonin available in the brain. Oversimplifiers call it the ‘happy chemical.’

Scientists in the United States, Portugal, and England, working with mice, found that its presence was vital for learning.

Scientists in the United States, Portugal, and England, working with mice, found that its presence was vital for learning.

As reported in the academic journal, Nature Communications, mice were presented with reward-driven, decision-making tasks. They were given varying amounts of time to make decisions (generally of what to do and where to go in order to get a treat).

Through optogenetic stimulation (a technique of using light to control certain cells which have been modified to respond to light) of serotonin neurons, researchers found that those mice with stimulated serotonin neurons made ‘wiser’ decisions and, broadly, learned more. But (and this is a big BUT!), those wiser, more circumspect learning patterns were only observed in mice that were given longer inter-trial intervals or breaks.

Mice with shorter inter-trial intervals relied only on their last encounter with the task to make their decisions. Mice afforded longer intervals between trials made choices that were reflective of the greater scope of multiple trials.

From Mice Lab to Horse Pen:

This research supports HorseHead’s long-held belief that dwell time is key to reinforcing what we convey to our horses.

Does your horse have time to make a decision or is it pressured?

“Humans and horses alike need reflection in order to make associations,” said Dr. Steve Peters. “If under pressure, the horse might only see and use one pathway. Essentially, it’s just reacting. But under the influence of serotonin and the emotional homeostasis that comes with the presence of serotonin, the horse is better able to review the whole reward history and to choose from it and show the optimal behavior. “

As horse owners and riders, it’s up to us to let the light shine through. That’s a geeky reference to the optogenetic stimulation used in the mice lab. Of course, we’re not keen on genetically modifying serotonin cells in horses’ brains. But we can set up an environment in which our horses get time to lay down neural connections and cement associations. We can let them learn by letting them be for a serotonin moment.

Dwell time augments outcome

When we use negative reinforcement to create a dopamine response (also known as ‘pressure and release’), we need to allow the horse to:

- Experience the dopamine reward (which may include licking and chewing, blinking, and head lowering) and

- Experience a serotonin release that is facilitating the horse’s brain as it connects past experiences with new ones and forms associations.

That’s learning happening. That’s neuroplasticity. That’s when good trainers get out their cell phones and reply to a text. That’s when you might grab a long drink of iced tea. That’s when you might say, ‘good job’ and put your horse away for the day.

Some Additional Notes:

There is no golden measure of break time. It’s not 10 seconds and it’s not one day. It depends and relies on your careful observation of your horse’s behavior. It relies on Feel.

There are micro-breaks and macro-breaks. Micro-breaks are the moments between requests. Say, for instance, you are working on haltering or working on opening gates: Micro-breaks are when the horse moves correctly and you release and pause. Macro-breaks are when you wrap up the training and stop for a day or more. Both are considered crucial to good horse work.

There are micro-breaks and macro-breaks. Micro-breaks are the moments between requests. Say, for instance, you are working on haltering or working on opening gates: Micro-breaks are when the horse moves correctly and you release and pause. Macro-breaks are when you wrap up the training and stop for a day or more. Both are considered crucial to good horse work.

Both dopamine and serotonin are essential neurochemicals in the learning process. Searching out the dopamine reward is foundational to the reinforcement learning strategy and the serotonin release during the break allows you to connect and make new associations to previous moments. Adds Dr. Peters: “This period of reflection is optimal when there is no competing stimuli — no new requests, or visual or auditory distractions.”

Read more about Positive Training and Negative Training

Not boredom, active learning! Amy Skinner lets her horse soak a moment

Really glad to see this. Dopamine has become a catch word. Also huge implications here, as we know beyond horse world. Learning theory has so much healing potential for horses and humans, especially children experiencing life situations which keep them in fight, flight or freeze, handicapping their learning ability and future life choices.

I’ve been delving deeply into +R (positive reinforcement) rather than pressure release techniques and have come to understand that there is a lot more going on in the brain neuro chemically than just dopamine, especially in teaching intrinsically rewarding functional movement and allowing my horse autonomy to choose to participate or not, which is pretty much heresy in horse world. (Not that a horse learning to move away from pressure doesn’t have its place.) but I’m looking for a change in attitude and willingness to participate and needed something more. Endlessly fascinating. I think we are still just scratching the surface of best welfare practices for our equine partners.

Kerry,

Keep up your experimenting with this approach. The more we are coming to understand about the activation of the horse’s neurochemistry and what may be optimal states of learning will indeed lead to improvements in the horse’s welfare as our communication becomes more clear. There are a number of horseman I know who are leaning in this same direction and newer research suggests that this facilitates neuroplasticity and reduces the involvement of sympathetic nervous system stress.

I wonder what your thoughts are, especially given this article, on the idea that licking and chewing “means” the horse learned or understood something. I recall reading a study that basically said that licking and chewing were autonomic responses to the removal of a stressor. They demonstrated this by using a loud unusual sound as the stressor in a barn full of horses — no visual stimuli or anything like that. The horses demonstrated an alarmed response to the sound, then very quickly started licking and chewing when the sound stopped. Obviously, in this scenario, they had not “learned something”, and yet those actions were there. I have therefore personally reasoned that the licking and chewing might have evolved as external, visual markers to let other horses know that “the threat is gone”. Just my own theory. Now, I believe the horse could be learning something and then also exhibit licking and chewing when the stressor (pressure) is removed, so the two are not mutually exclusive. But, I don’t agree with the many people who say that if they lick and chew, it means they understood what you were trying to teach them. Thoughts?

Susan,

It has been my experience that the licking and chewing comes right after a dopamine release. The pressure (loud noise) triggers the horse into the sympathetic nervous system, cortisol is released, stress, fight flight mode, stomach is turned off, no digestion…Pressure is released (no loud noise) horse transitions from sympathetic nervous system back into the parasympathetic (stomach is activated) salvatory glands are activated, dopamine released and then the horse licks and chews…I have set this scenario up thousands of times and its the same each time..Some horses can transition faster from sympathetic to parasympathetic while other more cautious horses this may take several minutes to transition.. I don’t feel that the Licking and chewing means that the horse actually learned anything particular…its the visual marker of the horse transitioning back into the parasympathetic nervous system…I do feel that this is the learning circle…pressure activates the horses brain into the sympathetic nervous system (pressure is the invitation to solve the issue) decisions are made in the brain, if the horse is not able to down regulate the pressure it will then trigger into an instinctive REACTION…..more stress and cortisol……if the horse can down regulate mentally then the horse can make a RESPONSE…which leads to the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system…which triggers the dopamine release which feels oh so good to the horse…which rewards the horse for the RESPONSE rather than the REACTION…therefor the horse will WANT to learn and do more that leads to relaxing and dopamine releases…..anyway…thats my $5 bucks worth! Hope that helps…or it may just add more confusion 🙂

That is the best explanation I have ever read on the whole process. Thank you!

I’m asking this question again but more clearly this time I hope. When you refer to treats (like a carrot for example) I have heard that it keeps horses in the dopamine phase and not progressing to the serotonin phase of learning. Do you have an opinion on treats being different than the release of pressure only?

Good questions on our blogs! Thank you.

I wish I could be more precise in answering them. In my experience, much of the professional opinion around this area of training is speculative. There are a lot of people who weigh in with “authority” but what supports their authority? Empirical evidence? Laboratory science? It’s difficult to know, for sure, how horses’ brains are firing/learning/absorbing/advancing. Ultimately, it will rely on your close experience with your horse and what you observe and what progress you make through good ol’ trial and error. Brain science and operant conditioning are just small tools in the big, ever-expanding tool box of good horsemanship. Enjoy the ride!

Glad to see this inclusion of serotonin in the discussion. Urge everyone to read any/all by heavyweight neuroendocrinologist Rob Lustig; his book The Hacking of the American Mind is vital info.

Little has been mentioned abt the fact that dopamine is addictive and requires constant increase in dose.

Dr Lustig talks abt the difference between pleasure and happiness; I feel this is evident when comparing a horse “lacking and chewing”, head hanging, and the horse that feels its true partnership with a human.

In short, while we fill our cortex ‘s need for constant stimulus through data by studying neurophysiology, it is important to watch what master horsemen of all disciplines have been doing for centuries.

Then watch the neurophys naturally happen….

Hurray for the inclusion of serotonin!